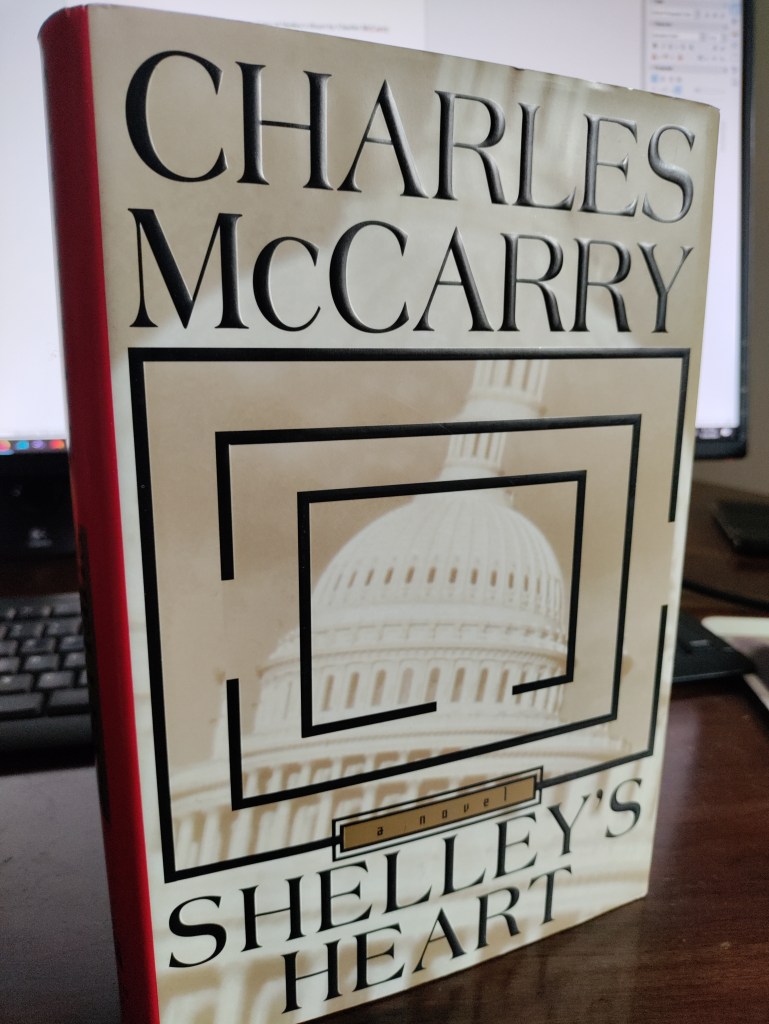

Here’s a picture of my copy of Shelley’s Heart by Charles McCarry.

It’s a first edition hardcover, but the second copy of the book I’ve owned. A few years ago I picked up and started reading a trade paperback edition, but I felt like the book was making me insane so I shelved it and, eventually, in one of my cataclysmic library-thinings, got rid of it. But recently, the book resurfaced in my brain and, on a whim, I grabbed this copy from a local used book store with a pretty deep Suspense/Thriller section (their Classic Literature section is shriveled but you can find some gems; ditto their ‘contemporary fiction’ zone; like many southern bookstores it has an enormous Religion section, but no interesting religious books; but it’s a good little store overall and you can find some tasty deep cuts with a bit of patience).

I first heard about McCarry in 2021, a year spent reading, almost exclusively, books in the mystery/thriller/suspense genre. Can’t spend much time in that field without encountering Otto Penzler, huge advocate for the genre. Penzler, somewhere or other, sang McCarry’s praises, so I looked him up, and found that he had other fans, including Jonathan Yardley, who I guess is an actual book critic but who I knew primarily as Frederick Exley’s biographer and a Book-Blurber, a Guy Whose Tastes Align with Mine Reasonably Often; I’m not going to look up the exact quote of Yardley’s because I am deeply afraid of spoiling the plot of Shelley’s Heart for myself, (and if I spoil the plot I won’t be able to go on reading it; the sheer vertiginous unpredictability, the never-knowing what the next chapter or, indeed, paragraph in Shelley’s Heart will bring, is what gives this Really Fucking Weird book its compulsive readability despite its pretty apparent, pretty persistent flaws), but it is something to the effect that Shelley’s Heart is the best novel ever written about Washington D.C.

So taking all that into account, it is not surprising to hear that Shelley’s Heart is a political thriller. Published in 1995, it is about a fictional presidential election, the first of the 21st century, so there’s an Infinite Jest-esque near futureness to it (about which more in future installments). It’s a bitterly contested race between Frosty Lockwood, left-of-center liberal of Lincoln-esque physique, and Franklin Mallory, steely-eyed conservative super-business-genius. Lockwood wins, but the plot is set in motion when Mallory confronts him with seemingly solid proof that the election was stolen through hi-tech voter fraud.

McCarry, before reincarnating himself as a writer, worked for both the CIA and the government at different times. As a young nerd he was a speechwriter for Dwight D. Eisenhower before hopping on for Nixon’s 1960 presidential campaign; later in life he wrote a biography of Ralph Nader called Citizen Nader.In an article for the Washington Post called“Between the Real and the Believable,” an interesting piece written in 1994, just as McCarry was wrapping up Shelley’s Heart, he says this about his transition from the political life to the writerly one:

For a decade at the height of the Cold War, I worked abroad under cover as an intelligence agent. After I resigned, intending to spend the rest of my life writing fiction and knowing what tricks the mind can play when the gates are thrown wide open, as they are by the act of writing, between the imagination and that part of the brain in which information is stored, I took the precaution of writing a closely remembered narrative of my clandestine experiences. After correcting the manuscript, I burned it.

What I kept for my own use was the atmosphere of secret life: How it worked on the five senses and what it did to the heart and mind. All the rest went up in flames, setting me free henceforth to make it all up. In all important matters, such as the creation of characters and the invention of plots, with rare and minor exceptions, that is what I have done. And, as might be expected, when I have been weak enough to use something that really happened as an episode in a novel, it is that piece of scrap, buried in a landfill of the imaginary, readers invariably refuse to believe.

It’s an article worth reading, if you’re reading Shelley’s Heart, or interested in doing so,because it’s a McCarrian microcosm, a little Peqoud in which, in miniature, you can see all his writerly qualities, good and bad, sailing side by side in a compact coastal foray, before embarking with them all again on the much longer transoceanic journey that is Shelley’s Heart; you’ve got his concise, clean prose, the moments of seeming-honesty both straightforward & elegant, his light-touch wit, his sneering nasal old boy’s snark, semi-masked under a But Please Consider This debate club ‘reasonableness’ that can be quaint fun sometimes, but that’s more often patronizing and annoying, particularly when directed at women and people with different temperaments than his own; I think his good qualities are easily visible in the above quote; for his bad, read this, describing one reader’s reaction to a character in a book of his (not Shelley’s Heart):

Soon after this work appeared, I found myself at a dinner party in Northampton, Mass., seated next to an agitated feminist, who, like my unhappy character, was young and beautiful and a recent bride. Throughout dinner, she told me how much she hated the girl in the book, whose behavior she had found to be utterly unrealistic and an insult to women — “male chauvinist propaganda,” she called it.

I was not surprised by the onslaught. For a writer in America, going out to dinner is like living as an American in Europe: Total strangers think they can say anything they like to you. Still, I had trouble grasping the point. Why did a 1950s fictional character have to conform to an ideological model that had not yet been invented at the period in which the novel took place?

On the front of my copy of Shelley’s Heart is a photo of the Capitol building; inset within it, in a black square with a single entrance, is the same photo of the Capitol, albeit smaller, and with its own, smaller single-entrance black box; within that is the same again, smaller again; and again once more. The weird sepia tone of the Capitol photo evokes the grain of CCTV footage; the boxes make you think of mazes, or of hierarchies, or give the sensation of pressing deeper and deeper into some inner sanctum, passing tests until you reach the Center…

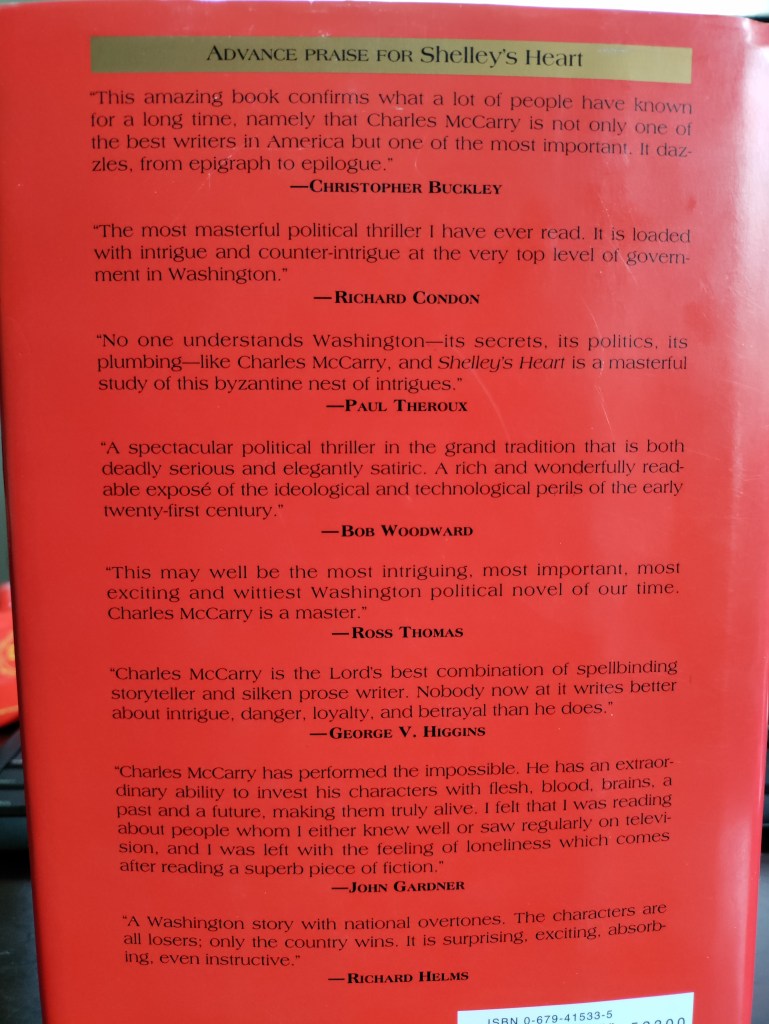

Here’s the back cover, given over wholly to Advance Praise:

Let’s break down this rogue’s gallery. You’ve got:

- Christopher Buckley, son of William F. Buckley, Jr. Christopher’s the guy who wrote Thank You For Smoking, among other things. He was also the chief speechwriter for George H.W. Bush during his Vice Presidency. Looks like a dweeb, went to Yale.

- Richard Condon, author of The Manchurian Candidate. Don’t know much about the book, but I know what the term ‘Manchurian Candidate’ means. Wikipedia also tells me that McCarry is an admirer of that book.

- Paul Theroux, popular novelist and travel writer, the ‘Lawful Good’ Theroux brother. He seems like the odd man out personality-wise amongst the blurbers, but it’s a name many in 1995 would recognize, I guess. Maybe he’s written thematically-adjacent stuff, he’s one of those prolifics who has a whole second wikipedia page for their bibliography to unfurl across.

- Bob Woodward, name I know, a face I don’t. Reporter on the Watergate Scandal for the Post, and wrote like four books about the George W. Bush presidency; he had a big hand in the Post’s coverage of 9/11, for which the outlet won a pulitzer in 2002 (lol).

- Ross Thomas, a crime fiction author about whom I know very little. Wikipedia is not helpful here other than to point out he wrote the “McCorkle-Padillo series,” which sounds like it should be the name of some tedious sequence of integers that all share some obscure mathematical characterstic.

- George V. Higgins, lawyer-turned-hugely influential crime/thriller writer, best known for the phenomenal Friends of Eddie Coyle. MA from Stanford, described as a “raconteur” by Wikipedia, which who knows what you have to do to get that to happen.

- John Gardner – presumably the British crime novelist, not the American writer who debated with William H. Gass, wrote Grendel, etc. This Gardner wrote plenty of original stuff, but also’s one of those authors who wrote their own James Bond stories.

- Richard Helms, political official and diplomat who was head of the CIA in the late 60s/early 70s. Definitely a nerd, probably a huge piece of shit. Looks like a less jowly Nixon.

There’s a precis on the front & back jacket flaps. When Against the Day came out and it was implied (but I don’t think ever confirmed) that Pynchon wrote the jacket copy, it never occurred to me that the authors themselves ever wrote their own jacket copy; ever since though I wonder. It’s possible, McCarry wrote this copy. It’s obviously glowing and sales pitch-y, and McCarry comes across (sometimes, anyway) like the kind of guy who would talk up his own stuff; although the specific hyperventilatory tone here doesn’t jibe with his generally cool, lightly mannered – “silken,” to use Higgins’s adjective – style elsewhere. It says of the election fraud scandal at the heart of Shelley’s Heart:

From this crisis, master storyteller Charles McCarry…has woven a powerful new novel that has been acclaimed even before publication as a masterpiece…”

We already looked at the back cover blubs but McCarry himself also offers a related tidbit in the aforementioned Post piece:

Not long ago, an old Washington hand, whom I had asked to read the galley proofs of my forthcoming novel about Washington and the management of a wholly fictitious constitutional crisis, phoned me in a dudgeon: “You’ve written about the way this town really is, and after looking into this mirror I’m not sure I want to go down to the office anymore.”

Back on the jacket flaps, the summary continues:

Shelley’s Heart is so gripping in its realism and so striking, even frightening, in its plausibility that McCarry’s devoted readers may have difficulty remembering that this tale of love, murder, betrayal, and life-or-death struggles for the political soul of America is a work of the imagination rather than an act of prophecy.

You could read those words “love, murder, betrayal” as another argument in favor of McCarry himself being the penman. They echo a list of his in a piece he wrote called “A Strip of Exposed Film,” published in a book called Paths of Resistance: The Art and Craft of the Political Novel, which gathers, from what I can gather, essays about political novels by various writers, those writers being McCarry, Marge Piercy, Isabel Allende, Robert Stone (writer of David Berman’s favorite novel, Dog Soldiers), and…..Gore fuckin’ Vidal! (This is a book I’d like to own). McCarry says:

The best novels, I believe, are about ordinary things: love, betrayal, death, trust, loneliness, marriage, fatherhood.

Perhaps at least whichever marketing intern or whoever absorbed this or other similar sentiments from McCarry before drumming up the copy, which also promises:

an ascetic, ideology-driven Chief Justice

an intriguing gallery of forceful women

an upper-crust secret society

and, last but most enticingly, that:

Above all, out of this crowd of extraordinary men and women emerges one person of striking originality, power, and all-too-human proclivity who will long remain in the reader’s memory.

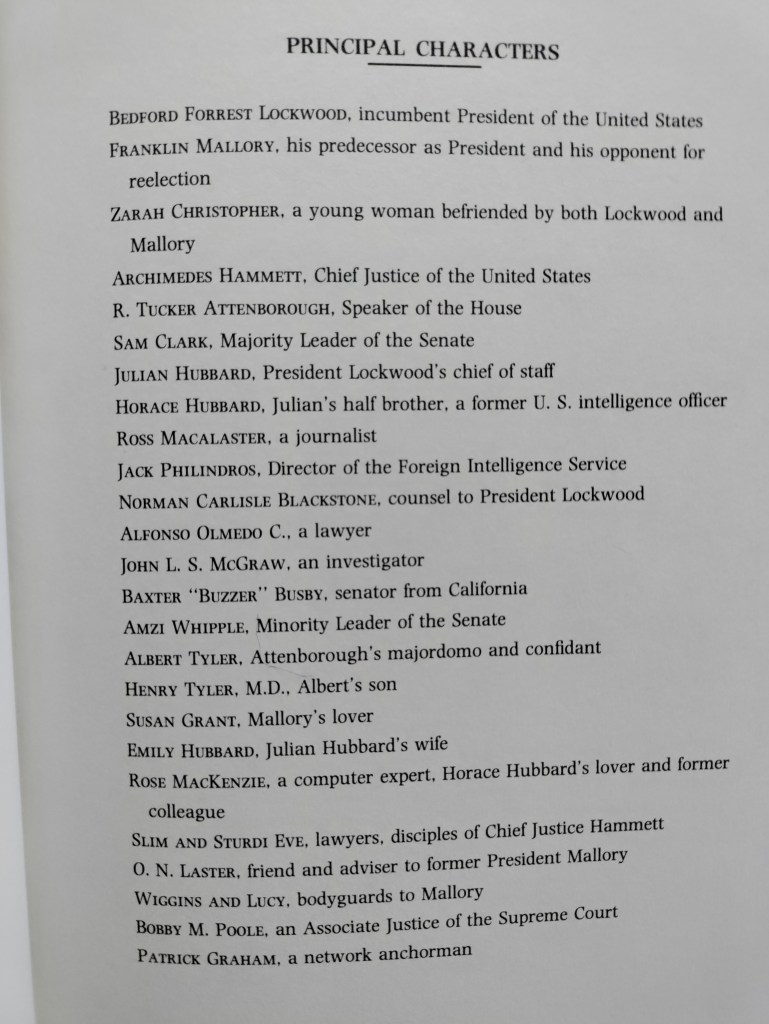

Relatedly, one last prolegomenon worth noting about the book is that it includes, before the text proper, a Dramatis Personae, and quite a dramatis personae it is; get a load of these names:

As I write this overture, I’m actually about a third of the way through the novel, and I’m not sure who the “person of striking originality, power, and all-too-human proclivity” is yet.

Next time: starting the book proper, and discussing Parts 1 and 2.