Note on Current BSBC Methodology:

There are two intended audiences for Batshit Book Club: the first and primary audience is someone interested in learning about uniquely bad books in an impressionistic way; plot summaries bore me to write & don’t make sense to me in the context of a book discussion, so I’m focusing here on specific elements – characters, passages, isolated events – that I find interesting, rather than doing a Let’s Play-style blow-by-blow of the plot. I want to convey the flavor of the experience of reading the book, not a scholastic gloss on it.

Which opens the door for the second intended audience: someone who has read/is reading the book in question & is seeking a fellow sufferer out in the shoreless wilds of the internet. The chances of you meeting someone In Real Life who has read Shelley’s Heart are slim to none; the chances of such a person wanting to discuss, at length, a niche, problematic, irregular book slimmer still. If you were close to buckling under the book’s insanity, and you went looking for someone else who has read and kvetched before you, and were shocked to find so few negative opinions about this highly fucked but still compelling book, this post is also for you.

Structure-wise, the only strictures imposed on what follows, and that will be imposed on future entries too, were that the words/thoughts must pertain to/develop from the portion of the book under discussion. Beyond that, ideas and riffs were permitted to develop as they would, with relevancy being the only real criterion for culling, and tangents allowed so long as they were rooted in the material at hand.

That being said, while the plot will not be discussed beat by beat, it will be brought up, and excerpts shown, etc. so if you’re worried about spoiling the book under discussion I would not recommend reading this or any other Batshit Book Club post.

There’s something particular & arcane about first paragraphs. If you go back to a novel’s first paragraph periodically, as you proceed further into the book that follows, you’ll begin to see whorls & patterns within it, aesthetic imprints & prognosticates of the artistic thrust of the thing as a whole. Here’s the opening paragraph of Shelley’s Heart:

It had snowed the night before the Chief Justice’s funeral, paralyzing the city of Washington and closing down the government. Now, at midmorning, the sun shone brightly, transforming the brilliant white mantle that covered Mount St. Alban into slush. Snowmelt from the roof of the National Cathedral flowed from the mouths of gargoyles, drowning the hushed notes of the organ that played within. Franklin Mallory, a lover of music (“like other Huns before him,” as some opposition wit had written when he was President of the United States), recognized the strains of Johann Sebastian Bach’s D minor toccata and fugue. Mallory found this famous work untidy and illogical and annoyingly reminiscent of Buxtehude – but then, organ music in general made him impatient. Like the rhetoric of his political enemies, it was overwrought.

Here, the part certainly contains the whole. With readerly loupe you can see here, in miniature, the various forces that jockey for control of Shelley’s Heart on a page-by-page basis.This is a novel that roils, whose entire tonal texture changes from chapter to chapter; Shelly’s Heart is an absurd political thriller that also wants to be a textured, philosophically serious Novel, and that takes itself and, more problematically, certain of its characters, very, very seriously.

One character in particular. You meet him right away.

The first three sentences are adequate scene-setting, familiar, comfortable, competent, lucid, directorial – and then Franklin Mallory enters the story.

The Franklin Mallory Problem(s)

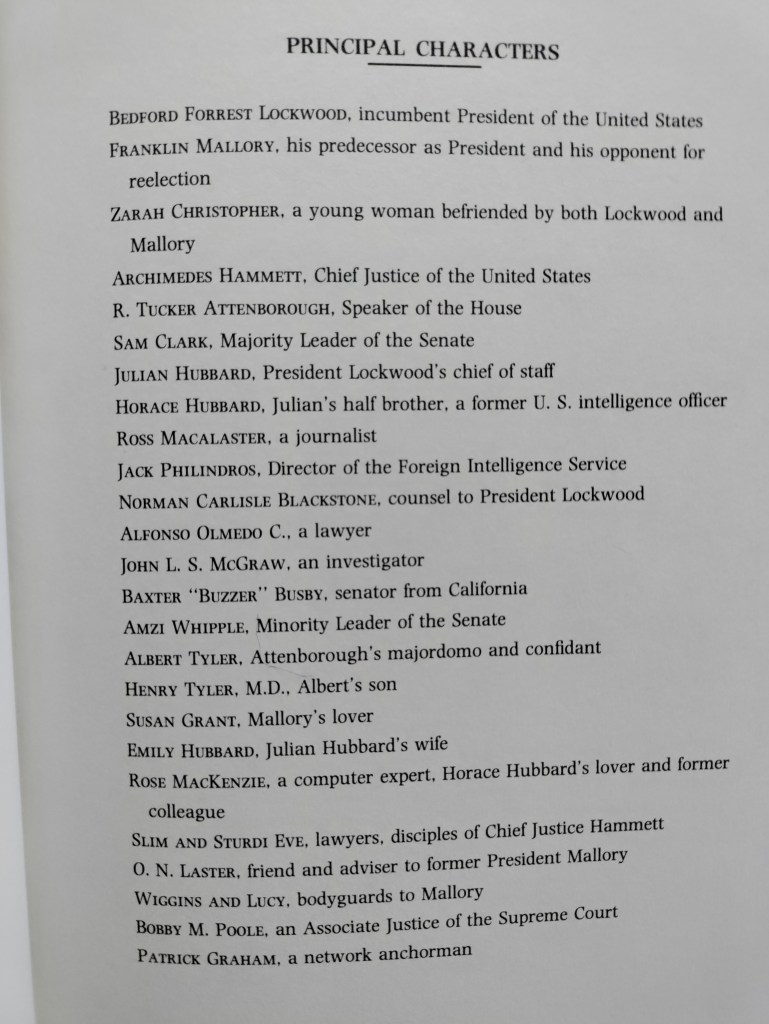

Franklin Mallory, former President of the United States, omnigenius, silver fox, hyper-businessman of near-future America, is a problem. He’s an excruciation, a fatiguing, obnoxious, tedious, implausible dingus that the book (and McCarry) takes very seriously. Think of any of the self-aggrandizing humorless bores standing in for protagonists in any Ayn Rand atrocity, and you’ll be close to the mark. If, like me, you’re a creator & connoisseur of imaginary enemies, Mallory is the kind of character that some of the worst hypothetical guys you can fabricate would cite as their favorite character in literature. He’s like Johnny Truant for libertarians.

The back half of Shelley’s Heart’s first paragraph gives you the terrifying triskele at the center of Mallory’s personality: pomposity (“lover of music” c’mon), positively diarrheic distribution of personal beliefs and philosophies, and unerring conviction in his superiority & correctness. Here he is, right off the bat, taking on Bach, Buxtehude, and his political enemies all at once:

Mallory found this famous work untidy and illogical and annoyingly reminiscent of Buxtehude – but then, organ music in general made him impatient. Like the rhetoric of his political enemies, it was overwrought.

But the Franklin Mallory Problem is not that he’s unlikable; it’s that the book itself favors him quite obviously, estranging him from the reality that it’s seeking to convince you exists. Most characters in Shelley’s Heart are permitted to have opinions, but no other character’s opinions are so freely distributed, so uncritically presented, so transparently approved of by the author. There is acid in the way McCarry will present lesser characters’ beliefs and hangups, but never with Mallory, even at his most outre. Look, here’s Mallory on Gender, both in and out of business contexts; after a paragraph of pap McCarry ends, not with any sort of rejoinder, critique, even the lightest irony to impugn in any way Mallory’s philosphy; instead throws in a dry little jab against feminists (feminism comes under attack constantly in this book, to full-body-cringe-inducing effect in later sections…)

Although Mallory was not religious in the usual sense, the notion that a man and a woman were the right and left hemispheres of an organism that had divided itself by mistake and was intended by nature to recombine exercised a mystic influence on his life. This was the reason why everyone who worked for Mallory did so with a partner of the opposite sex. He hired only young single people and permitted them to select their own workmates as they settled in. Once paired, they did not usually remain uncoupled in other ways for long. Like his business empire, his administration was almost certainly the most connubial since the Moonies of the late twentieth century. As he put it in a motivational equation reproduced on countless posters and lapel pins, ♂↔♀. Feminists referred to this formula as the Hyena Equation.

Worth noting: my correspondent in Batshit Book Club does not think Mallory gets especial authorial attention. And I don’t have documentary proof that McCarry favors Mallory. But every readerly/writerly instinct tells me that it’s so; maybe later developments in the book will prove me wrong, maybe Mallory is being set up the way he is for a collapse. But even if I’m wrong, Mallory’s preeminence inarguably lards what could be, what I would argue should be, an implausible but very fun political thriller with unnecessary, uninteresting, sometimes distasteful bullshit. McCarry seems never not happy to stop the plot and present some morsel of Mallory’s weltanschaaung; at best these moments are funny, but the funniness is mostly undercut by the sensation that you are the only one laughing, and that, in fact, Someone Important (McCarry) thinks Mallory’s shit is cool or admirable. Check out Mallory in his library:

Mallory finished his coffee and went into the library at the back of the house…He selected a book at random among the thousands on the shelves. The one that came to hand happened to be Lord Macaulay’s History of England. He had heard that Adolf Hitler, with whom Mallory was often compared by his detractors in academia and the more literary press, used to read only the last chapters of books. Mallory read them all front to back…

The radicals, Mallory believed, were a herd of demagogues driven by some primal instinct that had little to do with the mind. They were the Puritans of the present age, oppressing mankind in the name of their own moral superiority. How like they were to the earlier crowd…except they had not yet found their Cromwell. God forbid that every they should, he thought, in a sort of prayer to Macaulay’s memory.

Again, no other character gets such elaborate, explicit transcription of their thoughts to the page. Mallory’s theoretical opponents in the book, characters like Frosty Lockwood, Archimedes Hammett, et. al., have their personalities and peccadilloes enumerated at a distance (in the case of Lockwood), or with explicit disdain (in the case of Hammett and his retinue). Here’s Hammett throwing his hat into the ring on the gender question with a take not too dissimilar from Mallory’s, yet immediately undercut but character and narratorial skepticism:

“No offense,”Hammett replied, “but she’s a female. They’re born into an eternal CIA that’s been keeping files on the other half of the human race ever since Eve was recruited by the serpent.”

Coming from anyone else, this statement would have merited at appreciative chuckle. In this case, Julian remained silent because as usual Hammett was perfectly serious.

When Mallory’s in focus, the film flickers, you see McCarry’s silhouette on the naked vinyl screen beneath. Mallory is not a self-insert, but he is a mouthpiece, and in terms of narrative consistency that may be worse. In the case of a self-insert, the creator is subsumed by the created; by contrast, a mouthpiece channels a voice that comes from outside the book; the whole fictional world is ruffled by a wind blowing in from another dimension and you, the Reader, are aware that God, in this case, is just a chinless guy from Pittsfield MA.

Honestly, any piece on Shelley’s Heart could consist solely of Franklin Mallory’s Greatest Shits.

The Future is Here and It’s Insane

Shelley’s Heart was published in 1995 but takes place in 2000; so, like Infinite Jest, Shelley’s Heart depicts a near-future America – not a distant dystopia, but a half-plausible, half-exaggerated Soon to Be, extrapolated from perceived trends at the time it was written. And like Infinite Jest, it’s sometimes prescient in a broad stroke way, while charmingly stuck in its own time with regard to particulars.

All fictional futures require some suspension of disbelief, but the demands Shelley’s Heart makes in this regard are peculiar and interesting. The sociological, scientific, and environmental changes it purports have happened between, say, 1990 and 2000 are, to put it plainly, fucking wild. Here are the four major ‘accelerations’ that Shelley’s Heart posits:

- Franklin Mallory has landed astronauts on Ganymede, one of Jupiter’s moons, and commenced mining operations there

- The Mallory Foundation pioneered a way to flush out fertilized ovum and store them in deep freeze. Free clinics, colloquially called Morning After Clinics, exist across the country that do this in lieu of abortions

- Thanks to the “animal rights lobby” animals are fucking everything up; there are more examples later in the book but early on we read this: “In Washington, [wild deer populations] had practically denuded the parks and traffic circles that had formerly beautified the city, and were now in the process of killing off the deciduous trees by eating their bark.”

- The CIA no longer exists “after it collapsed under the weight of the failures and scandals resulting from its misuse by twentieth-century Presidents.” In its place there is now the Foreign Intelligence Service, started, of course, by Franklin Mallory during his Presidency, and with a Director appointed by himself and the Senate at the time, but don’t worry, it is very different from the CIA and much more ethical, because it is “governed by trustees, independent of the President.”

Even further into the book, it’s hard to determine which of these things – any one of which could provide impetus to any number of plots or sub-plots – are going to be important going forward. It’s hard to imagine a book that imagines Ganymede being settled in 1999 but that somehow doesn’t involve that in its plot whatsoever, but that’s a distinct possibility in the decidedly terrestrial Shelley’s Heart. At the very least it functions asanother feather in the Mallorian cap, of course.

Too, McCarry gives us glimpses into the societal texture of his 2000 A.D. America, but there’s disappointment here, because these glimpses feel less like glimpses and more like specific axes McCarry felt like grinding, jokes at the expense of things that obviously irk him (feminists, animal rights, environmentalists), and in the form of satirical, dystopically-inflected extrapolations. I talked about the animal problem above, but here’s how the feminist movement is going in Shelley’s Heart:

Hammett made a gesture to someone inside a Volvo station wagon that was parked at the curb with its motor idling. Two women dressed in ankle-length calico dresses and hiking boots got out of the car…One was blond, thin and willowy, with enormous blue eyes, like a Vogue model…her thin skirt blew around her long and unusually beautiful legs. Despite the weather, they were bare.

Macalaster said, “The skinny one is going to catch pneumonia.”

“Not her,” Hammett said. “She’s absolutely impervious to cold.” The other one…was rawboned and as tall and broad-shouldered as a good-sized man…she caught Macalaster staring at her friend’s legs and sneered in feminist disgust.

Meet Slim and Sturdi Eve, an ecolawyer couple who prepares all of Hammett’s meals with produce from their organic farm, and who are also his all-purpose spies and bodyguards. Their last name, “Eve,” comes from one of the weirdest fuckin’ McCarryian imaginings:

Among militant feminists the surname Eve had lately come into fashion as an alternative to what they termed their “chattel names” that had been imposed on them by the males who had impregnated their female ancestors…“She” had been considered as an alternative appellation, but it was rejected because it contained the name of the enemy – “he” – hidden within it. Finally they settled on the simple and beautiful alternative “Eve,” which was a sign of female infinity because it was spelled the same forward and backward.

This is Imaginary Near-Future Extremism as Really Weird Joke, I guess, and it falls so, so, so flat – but it falls grandly, dramatically flat, in a uniquely unhinged way – and that’s what makes Shelley’s Heart so compelling a whole, what makes it possible to go on about it for 2400 words & yet feel that you’ve barely skimmed the surface…..

Welp. There’ll be time to go deeper next time.

Next time on Batshit Book Club: Shelley’s Heart Parts 3-5, in which, to everyone’s chagrin, Franklin Mallory falls in Love.