Last week I discussed the point at which I lost all hope for a redeeming resolution in Shelley’s Heart. The book had been so bad, in such a narrow way, for so long, that it exploded my explorer’s optimism; but in that explosion a piece of shrapnel must’ve gotten lodged in some extremity because, somehow, even as I neared the long-awaited End, I began to think I believed that the plot would, despite everything, at least close out in a memorably bad way.

Well.

At the End of the Tunnel, a Wall

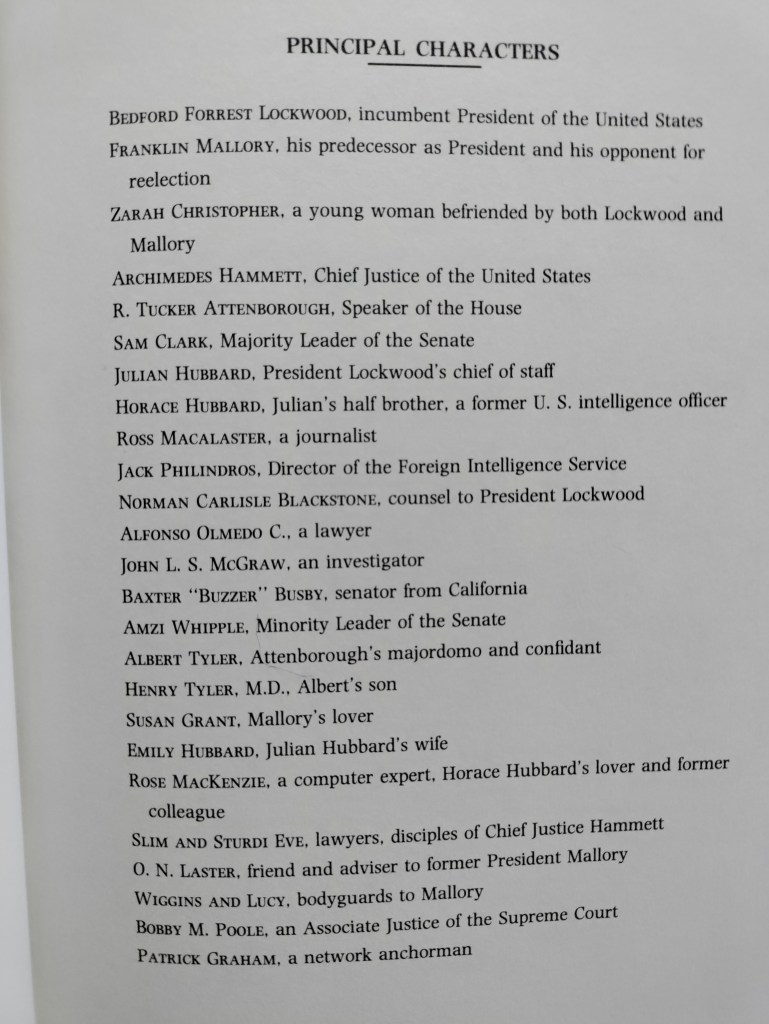

After 500+ pages of political thriller watered down with low-effort spy fiction, of absurd digressions, irrelevant sci-fi bombshells, reactionary political fantasia, of Slim and Sturdi Eve, Franklin Mallory, Zarah Christopher, and the rest of the cavalcade, McCarry closes out his faecum opus with a downward arpeggio of anticlimaxes, off-stage resolutions, and sanctimonious narratorial hand-waves.

There are artistic, deliberate ways in which books can be left unfinished. But you have to earn it, and Shelley’s Heart doesn’t earn it. A book as needlessly prolix asthis, that seemingly cannot help itself from dashing off on absurd digressions, or from underlining for the dozenth time its author’s specific crochets & hangups, cannot now be terse when the time comes to pay what even the most basic, plainest stories owe. I’ve seen fucking cave paintings with better story structure than this.

Of two of the main architects of the stolen election that kicks off the entire book, McCarry says:

It was not yet known what would happen to Julian and Rose MacKenzie.

That’s it! These are characters who have had whole chapters, whole sequences devoted to them, by the way, and they get dropped like toys. Others important characters don’t even get mentioned at the end: how about Alfonso Olmedo C., J.L.S. McGraw, Emily Hubbard, Carlisle Blackstone?

The reason, of course, is that McCarry didn’t know how to bring his diarrheal avalanche to a stop – not without expending another 100 pages at least. This is the inevitable, gnarly, particolored pileup that happens when you send so many clown cars in the same direction. And far be it from me to wish that Shelley’s Heart were a page longer than it is, but the simple fact is that, even if the novel’s general verbal indulgence is one of its chiefest flaws, this final trailing-off seems like a dereliction of authorial duty. This is not artistically acceptable vagueness. This is “I threw so much shit at the wall and none of its sticking oh God how can I sneak out of the house before anybody sees the mess I’ve made?”

Showdown at the Not OK Corral; or, Lucy & the Boy-Girl Machine Pistol

The courtroom-constitutional drama ends abruptly. The seemingly central question of the presidential succession following a stolen election are resolved lamely, tamely. These tepid sequences are the last fossils of the political drama this book, at one time, seemed like it would be about, but at some point McCarry decided he was more interested in the espionage and spy stuff, which has been encroaching on the core of the book for at least 100 pages, and whose mascot is Zarah, who you know is McCarry’s favorite because she gets to waste the two evil lesbian terrorists in a super cool shootout at the end that, in comparison to the final bits of political wrangling, is positively lavish in its production value.

Zarah, along with Franklin Mallory’s favorite boy-girl security people, Lucy and Wiggins (Wiggins!), end up discovering that Slim and Sturdi Eve (if you forgot: lesbian ecolawyer terrorists) were behind the assassination, early in the book, of Mallory’s last romantic partner, Susan Grant. Up until now everyone assumed the assassination was the work of a terrorist organization called The Eye of Gaza, and that Susan was unfortunate collateral damage in an attempt on Mallory’s life. But no, as it turns out, Slim and Sturdi, being radical liberals, purposely killed Grant because they discovered she was pregnant with Mallory’s child, and the thought of his political line being carried forward into a new generation was unbearable.

Once they put all this together, Zarah decides that she will pretend she’s pregnant with Mallory’s child, so that the deadly duo come after her. Which they immediately do, because when it comes to criminal acumen Slim and Sturdi are basically on the level of, like, Team Rocket. In her genuine Terrorist Caftan, Slim approaches Zarah, but Lucy intercepts her; she had been waiting in a nearby lake, underwater, like a ninja in an old anime [ellipses mine]:

Half an hour earlier, Lucy had swum across the lake underwater, her snorkel tube creating the beautiful ripple Zarah had seen from the clearing…Now Lucy saw the brilliant flash through the lake’s surface and rose to her knees out of the shallows in which she had been lying…Training had eliminated the need for thought – even, as Zarah had foreseen, for intuition. Holding her 6mm all-vinyl♂↔♀-issue machine pistol in both hands at the end of rigidly outthrust arms, Lucy fired a burst of 12 mercury-weighted, vinyl-tipped, soft copper rounds into the heart and lungs of the person who had killed Susan Grant.

Contra my own directives with Batshit Book Club, I’ve summarized the plot here, but I needed to in order to highlight that this book’s most notable, longest climactic scene involves the Tom Clancian tactical takedown of an ecolawyer-couple-turned-liberal-domestic-terrorist-cell. It’s all taken out very seriously, with a po-faced, unearned nobility, but McCarry, does allow himself to point out, one last time, that Slim is the hot lesbian in the couple, even in death:

With her pistol pointed at the corpse’s head, Lucy folded back the hood of the caftan. A shining cascade of hair spilled onto the damp soil. The face was quite beautiful in its wide-eyed astonishment, and to Zarah she looked very much as she had when she was enticing Attenborough, like an actress summoning up a former self to make the character she was playing believable.

Awkward Envoi

The final scene between those two icons of tedium, Franklin Mallory and Zarah Christopher, is laughable, both for bathos and brevity. It may be the shortest chapter in the whole book, occupying less than a page. Here’s the meat of it [ellipsis here belongs to McCarry]:

Zarah said, “I want to say this to you, Franklin. I wish your child had been saved.”

“So do I,” Mallory said. “How I wish you’d stay. It’s very hard to accept that there’s no chance of having the child I’ve waited for all my life.”

“I thought you knew that already,” Zarah said.

“Not in quite the impossible way I do at this moment. I’ve never thanked you. What you did, seeing the truth, seeing the obvious, walking into the woods that way and…willing your death not to happen.” He paused. “I just wish you didn’t want so badly to be”- he searched for word – “apart.”

“It runs in the family,” said Zarah. “Goodbye.”

Just the word, not the smallest gesture. She simply left. Watching her walk down the hill, so singular and uncaptured, he fell into a reverie, wishing for a child in which they could both go on living.

There are many things McCarry does wrong in Shelley’s Heart, but you gotta admit, perhaps never before in literature (certainly not since Ayn Rand) has an author so indelibly captured the nuance, poetry, and nobility of Libertarian Romance…

“The best novel ever written about life in high-stakes Washington”

I’m sitting here reading Jonathan Yardley’s 1995 review of Shelley’s Heart and relearning a lesson I somehow often let myself forget, which is that corporate journalists should never be trusted, on any topic. Check out the opener to Yardley’s review:

Not to mince words: Shelley’s Heart is an amazing book. The eighth novel by a writer who to date has been filed away in the pigeonhole of political suspense and/or spy fiction, Shelley’s Heart at once stays within the conventions of genre and soars above them. It is a work of immense ambition that comes astonishingly close to achieving everything toward which it aspires. In so doing it rudely elbows its way into the precinct of “serious” fiction, rendering by comparison almost everything that now passes as such pallid, lifeless and jejune.

And later:

McCarry’s publisher does him no service when it claims that “the intricate, intelligent plot and writing invite comparison with Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent and Fletcher Knebel and Charles Bailey’s 7 Days in May.” Perhaps that comparison will lure readers whose tastes do not venture beyond the best-seller lists, but Shelley’s Heart is to those two novels as “King Lear” is to “The Sound of Music” and “Barefoot in the Park.” The Drury and the Knebel-Bailey are hack entertainments; McCarry, even though he dares not venture beyond genre, has written a work of literature. Its plot is, as advertised, complex and smart.

As a reminder, Yardley is talking here about a book whose main villains include a pair of fanatical liberal ecolawyers thatassassinate pregnant women so they can’t give birth to conservative children. A book in which the environmental movement somehow resulted in feral animals running wild all over the country. In which, somehow, there are not just one, but multiple “radicals” in Congress.

Personally, if I were Frederick Exley, I would want someone else to have written my biography.

Paul Christopher, Play Us Out

Shameful admission: when I closed Shelley’s Heart, I felt an acute desire to find and read The Tears of Autumn. Tears is McCarry’s much earlier, most famous book, the second book to feature his series character Paul Christopher, father of the illimitable Zarah Christopher.

As a reader, as a person, really, I’m highly susceptible to enthusiasm. A habit I wish I’d never developed, one so deeply ingrained at this point that it’s less habit and more an element of character, is this endless hunger for reading blurbs, write-ups, reviews, recommendations, due to some unkillable and childlike belief that they mean anything.

It was Otto Penzler’s and Jonathan Yardley’s praise for McCarry that led me here in the first place – specifically Penzler’s, mystery/thriller maven that he is. And despite slogging through this 500-page scourge, and despite what I literally just said about not trusting journalists, I don’t know if I can rest without giving McCarry’s supposed masterpiece a try. Maybe Shelley’s Heart is the freak in an otherwise solid oeuvre…

So I did find a copy, and I have dipped into it. Not enough to render a verdict, but the forecast, based on these early pages, is a grim one. First paragraph and McCarry’s, um, eccentric approach to gender relations is on full display:

Paul Christopher had been loved by two women who could not understand why he stopped writing poetry. Cathy, his wife, imagined that some earlier girl had poisoned his gift. She became hysterical in bed, believing that she could draw the secret out of his body and into her own, as poison is sucked from a snakebite. Christopher did not try to tell her the truth; she had no right to know it and could not have understood it. Cathy wanted nothing except a poem about herself. She wanted to watch their lovemaking in a sonnet. Christopher could not write it. She punished him with lovers and went back to America.

And, a bit later on, we get an actual couplet from the days when Christopher wrote poetry. I think he made the right choice giving it up:

Desire is not a thing that stops with death,

but joins the corpse and fetus breath to breath…